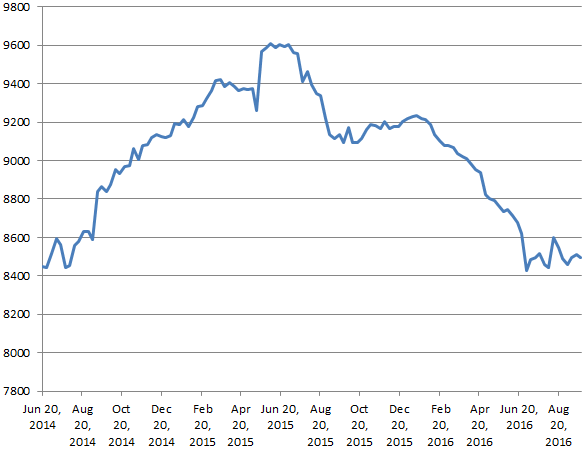

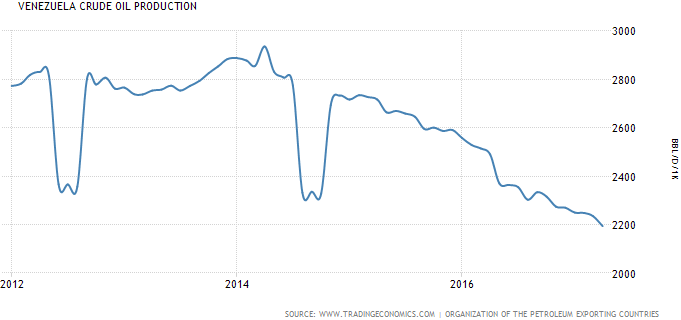

Our continual improvements kept domestic production on the upswing for more than a year after the price of oil started tumbling in June 2014. Over that time, the active rig count was dropping by almost two-thirds, assets were being sold off and the first waves of layoffs were occurring. Yet our oil kept flowing. It wasn’t until July 2015, eight months after OPEC made the fateful decision not to support prices, that U.S. output started experiencing a downward trend.

U.S. Crude Oil Production (thousand barrels per day)

By that time, the gutting of prices had been done. The increased productivity that resulted from the hydraulic fracturing (fracking) innovation converged with OPEC’s defense of market share to totally overwhelm demand to the point of pushing the price all the way down to $26 in February 2016. Adjusted for inflation, oil & gas were at historic lows. More asset sales, layoffs (by now numbering in the hundreds of thousands) and even bankruptcies ensued. Within OPEC, dissension started to stir.

As 2015 gave way to 2016, the non-Arab contingent of OPEC, who didn’t have near the savings to draw on during this market correction as Arab members, started to push for organized output cuts. Everyone had lost a piece of the pie to the shale producers, and were now possibly set to lose more as the U.S. government lifted the oil export ban in December 2015.

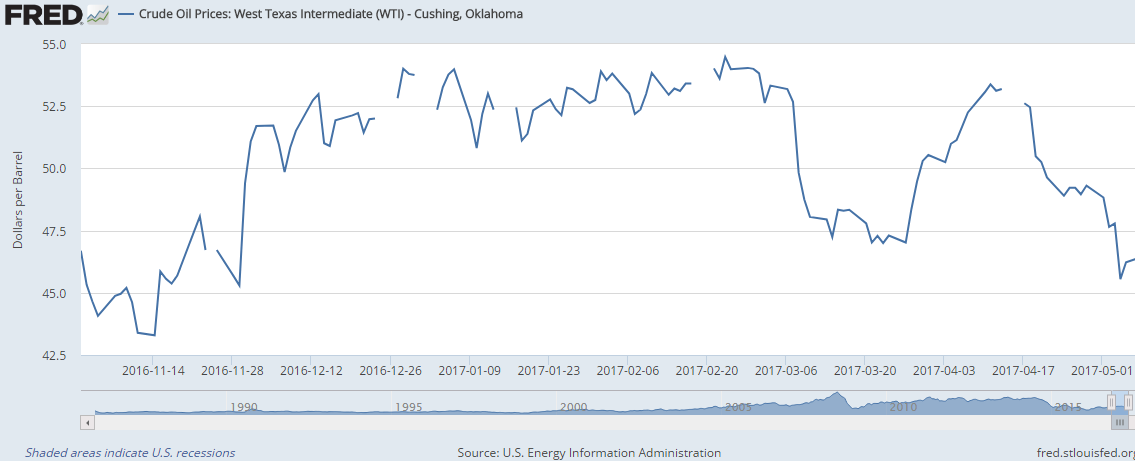

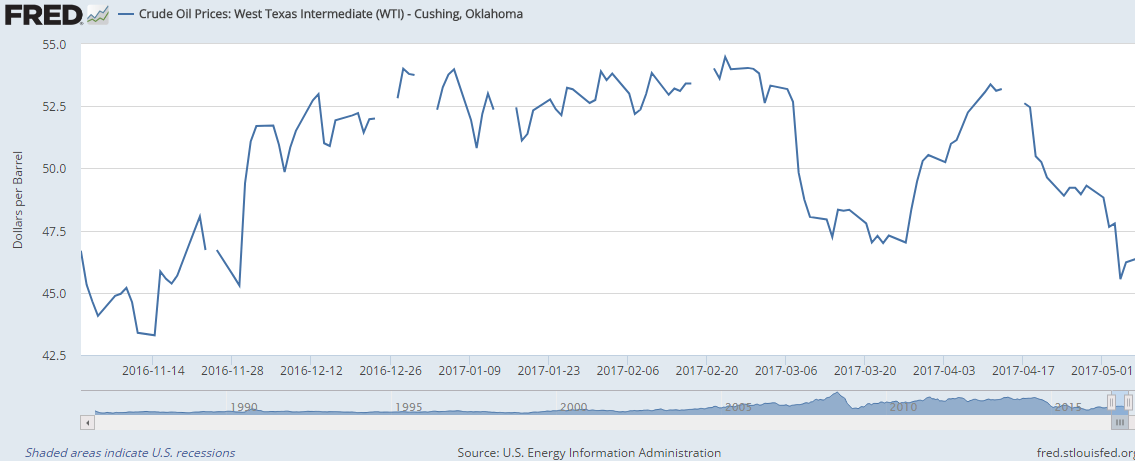

At last, in late 2016, as a slight recovery had already taken hold, OPEC & Russia agreed to remove more than a million barrels of oil per day from the market. Since then, the price has fluctuated around $50.

---

The Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries was formed in 1960 “to coordinate and unify … policies … and ensure the stabilization of oil markets in order to secure a … regular supply of petroleum to consumers, a steady income to producers and a fair return on capital for those investing in the petroleum industry.” It’s a cartel, something we don’t see in the U.S. because it’s illegal for firms to collude in price/supply fixing.

Oil is a perfectly competitive good. It’s a homogenous product in that it differs very little from one producer to another. ‘Your oil is like my oil is like his oil.’ A producer in such an industry is a price taker, and in a perfectly competitive market free of collusion, all profit is eventually drilled away. Moreover, as are many other commodities (agricultural products), oil is an inelastic good. Demand is less sensitive to price because food & energy are more valuable to consumers than say, another pair of sneakers or earrings or T.V.

Combine those two characteristics, and one motivation for OPEC’s formation becomes apparent. Add a flexible & nimble independent wild card like shale producers, and the result is the 2-year battle for market share from which we’ve only recently begun to emerge.

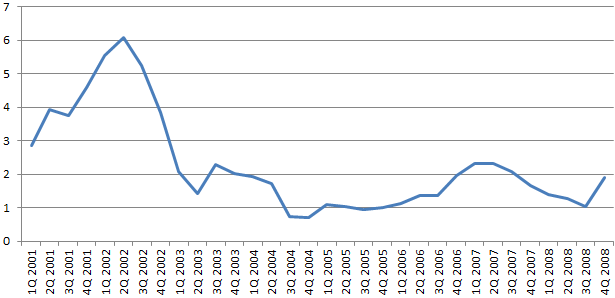

Perhaps the catalyst to OPEC’s current predicament was the growth of the developing world, the various international skirmishes & conflicts and dollar weakness during the dawn of this century. These forces came together to push the price of oil up to almost $150 in 2008. Compounding matters was the particularly low level of spare capacity it had, precluding its ability to bring the price down with more supply. This turned out to be the price signal that was needed to make fracking viable. And once that genie was out of the bottle, there was no putting it back.

OPEC Spare Production Capacity (million barrels per day)

---

From the current juncture, there are multiple directions price could go.

According to OPEC’s website, the oil industry makes up an average of almost half of the gross domestic product of member countries, and accounts for 90% of export revenues. Some plan, or have attempted to put their economic eggs into other baskets.

Under the direction of King Salman’s son, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, Saudi Arabia last year announced a plan with the goal of diversifying its economy so that it relies less on oil. It appears as much social advances (more women in the workplace and defanging religious police) as financial ones, the latter of which includes expanding their sovereign wealth fund into the world’s biggest, and selling almost 5% of the state-owned oil company, Saudi Arabian Oil company (Saudi Aramco).

If other countries succeeded in such efforts, as Nigeria has tried for a number of years in developing their digital economy industry & mining of other natural resources, the supply of oil could theoretically decline, as inputs such as capital & labor would be pulled in other, possibly more lucrative directions. That’s what shale producers are facing as they attempt to respond to a firming market; laid-off workers have moved on, in some cases picking up stakes & moving to other states altogether. This raises expenses beyond which some companies can afford. Hence, supply dries up, and upward pressure on oil prices is felt.

On the other hand, some non-OPEC countries have opened the door to foreign participation in their respective industries.

In 2014, Mexico did so for a small portion of its proven reserves, and a large chunk of exploration for new resources. There also may be opportunities for these firms to work with the state company, Petroleos Mexicanos (PEMEX). While down on the other side of the equator in Latin America, Petróleo Brasileiro SA (Petrobras), Brazil’s scandal-plagued, mostly-state-owned petroleum company, has fielded interest from Shell et al regarding the so-called pre-salt oil fields in the deep waters off its coast.

Even Russia’s state-controlled company Rosneft is selling off chunks of itself. And while Russia does have significant shale resources, international partnerships to exploit them ground to a halt as a result of diplomatic sanctions put in place after its annexation of the Ukranian territory of Crimea. As it is, the most prominent case of diffusion of fracking technology looks set to take off in the Vaca Muerta region of a more business-friendly post-Kirchner Argentina.

If such foreign direct investment bears fruit, it would likely introduce efficiencies into the sectors of the respective countries. Consequentially, they would realize the dropping breakeven points experienced here. Hence, more product would flow into the international market thereby pushing the price down.

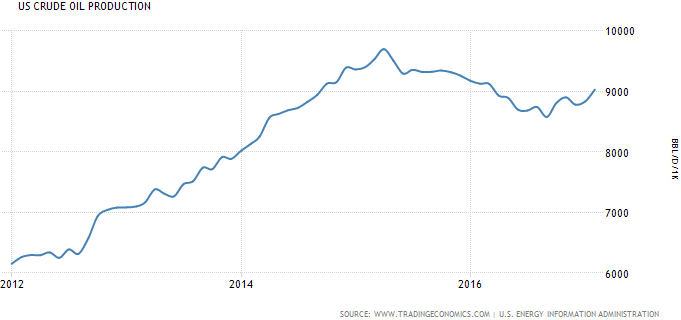

Conversely, if they suffered the same fate of asset seizure that many companies of varying industries have experienced in Venezuela (most recently GM), this would tend to restrict supply, sending prices in the other direction.

Venezuela is an extreme case in that it has been poorly governed under the late Hugo Chavez and his successor, Nicolas Maduro. They have so mismanaged the largest reserves in the world that they can barely afford to bring any to market. Theirs is a classic case of the distortions introduced into an economy by government meddling; their production should have been on an upward trend until prices tanked. As it is, they serve to put a floor under prices. And if Venezuelans continue to ramp up their dissent in the face of increased government efforts to ineffectively assuage (six hikes of the minimum wage in the last year!) and/or suppress it, the result could be something that causes further drops in production; armed conflict.

---

All the while, the U.S. shale producers have emerged as a new type of ‘swing producer’.

We have a comparatively stable society where the risk of armed conflict is low, and the chance to strike it rich with technological innovation is encouraged by the presence of intellectual property protection. And now, not only do we have the opportunity to export that know-how, but for the first time in a couple generations we can export some of our resultant abundance to the rest of the world (not to mention possibly a little more security to our allies, subsequently fostering more peace).

The lifting of the export ban enhanced efficiency by reintroducing the U.S. as a major international player, comprised itself of hundreds of autonomous participants. It provoked what was, for all intents & purposes, a free market response from OPEC in the fight for market share.

The evolving nature of our industry could actually serve to stabilize prices from here forward. As the Wall Street Journal reported a month ago, a recent 4-month trading range of oil was the tightest such stretch in 14 years.

Moreover, our industry isn’t directly burdened with the responsibility of funding the state; it makes up only 5-10% of our diverse economy. We have been able to produce more & more at less & less cost, while redeploying resources that got us here to the other 90+%. OPEC countries et al can no longer afford the higher breakeven prices necessary to support their relatively more bloated bureaucracies.

OPEC’s next official meeting is May 25th. It’s looking to be somewhat anti-climactic however, given the signs they have been sending lately pointing to continuing the cuts instituted last November. While we are certainly witnessing the end of the old OPEC, the organization itself probably isn’t going anywhere. Given its recent outreach to Egypt & Turkmenistan, not to mention its closer cooperation with Russia, its ranks might actually swell a bit.

U.S. shale producers aren’t going anywhere either. In fact, we’re likely going to keep on improving. Just the other day, I toured a 2-year old rig that’s even more nimble than our 4- & 5-year old rigs. Technology does not recede; it only advances.

In the past, some of the U.S.’ competitors blamed ‘the Great Satan’ for theirs & the world’s ills. Ironically enough, they would be correct this time, but for all the right reasons.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed