So far, I like what I see. “Impact of Government Borrowing” is a new chapter for us. It strikes me as a way to beef up the “Fiscal Policy” chapter with a discussion of consequences.

As one who values the freedom and liberty codified in our constitution, I used to think it might be a challenge to cover the policy chapters. It’s in those chapters where economics becomes more intertwined with government and politics, and the voters who drive them, some of whom sit in my classroom.

Over time however, it’s become apparent to me that the topic speaks for itself.

This came to mind when I happened upon a passage recently from another textbook, “Modern Principles of Economics” by Tyler Cowen and Alex Tabarrok, professors at George Mason University and fellows at the Mercatus Center. I actually use some of their videos in my classes. The topic was fiscal policy over the course of the business cycle.

The authors allude to Keynesianism, the practice of increasing government spending during a recession in order to fill the resulting gap in aggregate demand. Some, like unemployment benefits, food stamps (SNAP) and health insurance, happen automatically. Our society has come to accept such short-term aid as a small cost of living in a prosperous, relatively free-market economy which is naturally susceptible to cyclical downturns.

Occasionally efforts are also made to include job training, public works, etc. History does not look fondly upon the results however, when the discretionary extras come to life, and any of it lingers.

In response to the Great Recession, Presidents Bush (W) and Obama signed off on $1.5 trillion in spending to bail out financial institutions, auto makers and prop up the economy in general. The federal government also regularly extended unemployment benefits to 99 weeks.

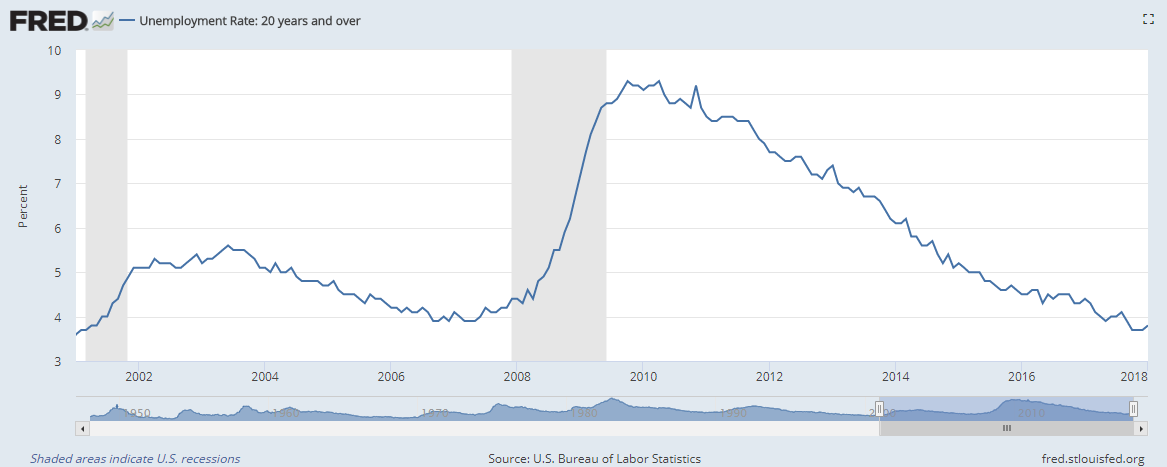

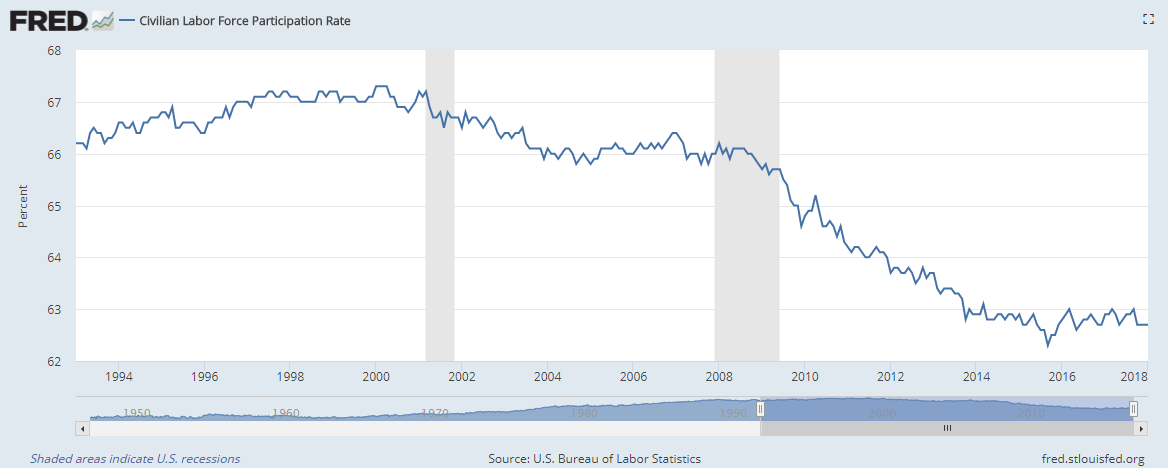

From 2008 - 2011, the federal budget deficit measured almost 8% of gross domestic product (GDP), on average annual spending increases of 7%, according to Office of Management and Budget data. In that time, the unemployment and labor force participation (LFP) remained under strain; the former hovering just under 9%, the latter starting its slide to a historical low of 62-63%.

Unfortunately, the LFP continued to drop as well, though not as solely attributable to the retirement of Baby Boomers as some might suspect. Around two million people had dropped out of the labor force and filed for disability, a program that itself has experienced increased payouts since criteria were loosened in 1984.

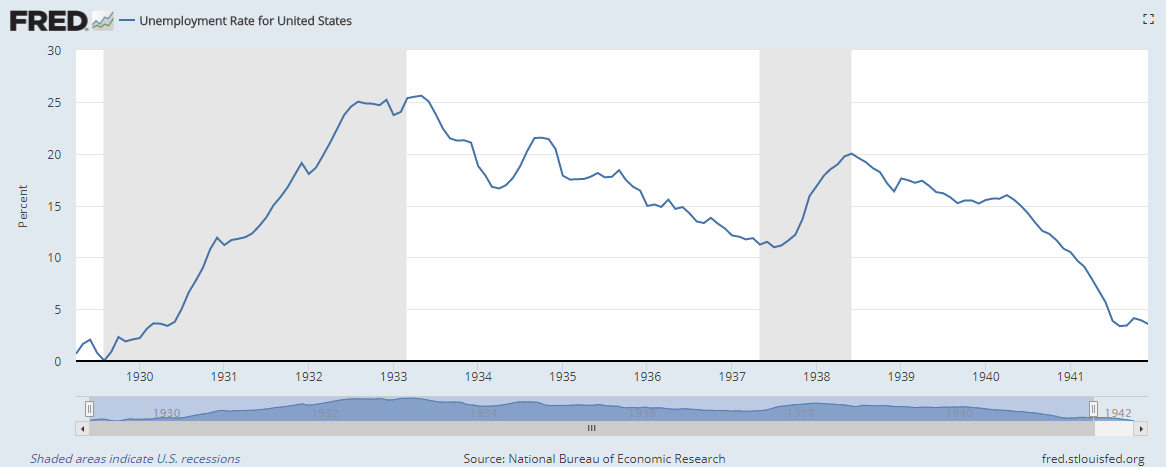

Over the course of the last ten years, we’ve been told that such spending measures were necessary to avoid another Great Depression. Back then, after an initially modest spending response, a fiscal explosion took hold.

Despite having approved of $500 million in the summer of 1929 to help farmers suffering from falling crop prices, before committing any more taxpayer resources, President Hoover first tried to cajole industry leaders to resist natural market forces in the aftermath of the stock market crash. He would eventually agree to $5 billion in aid to businesses and state and local governments in 1932.

This paved the way for average annual spending hikes of 13-14% for the balance of the 1930s, the nature of which resembled a rollercoaster ride; spiking beyond 28% in some years, while dropping a couple percentage points in other years. The budget deficit averaged almost 4%.

It was in this era when John Maynard Keynes wrote “The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money” (1936), thus giving rise to the aforementioned school of thought. The spending embodied by the “alphabet soup” of government aid to the economy fit nicely into this new way of thinking. Attempting to “pay the bills” at the same time conversely, did not.

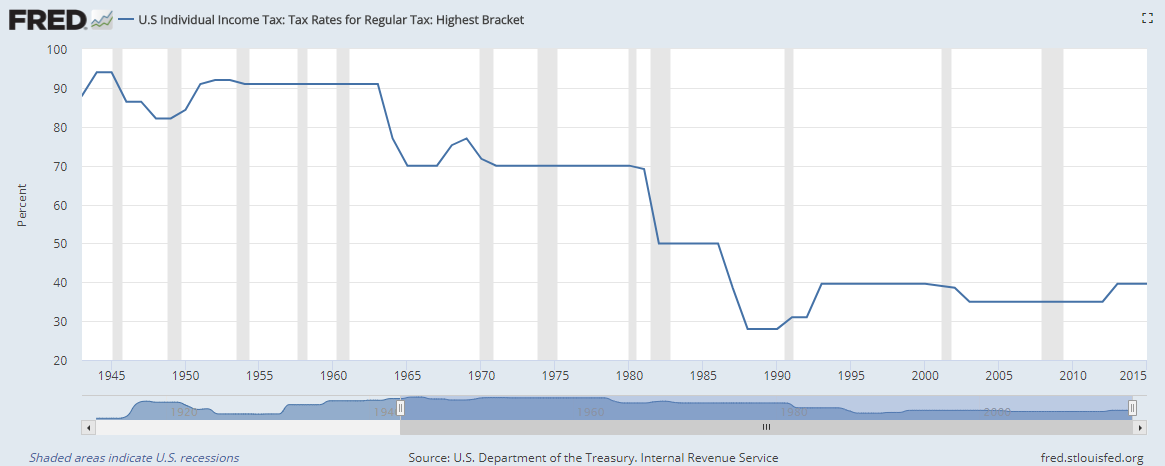

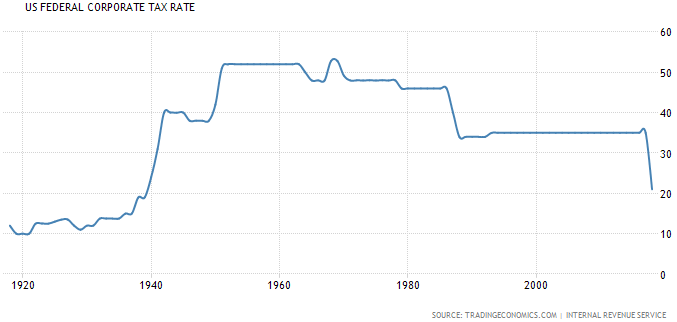

Once Hoover resigned himself to the position that government intervention was necessary, his instincts to balance the budget followed. Having already raised taxes on consumers by way of the widely criticized Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930, he approved raising a variety of taxes in 1932, the top rate on income more than doubling from 25% to 63%. As he did with spending, President Roosevelt (FDR) took the baton from Hoover and raised taxes even further in 1935 and 1936.

The economy subsequently struggled nearly the whole decade to return to where it was before the downturn in terms of nominal GDP, and unemployment fluctuated between 15-20%, spiking to almost 26% at one point.

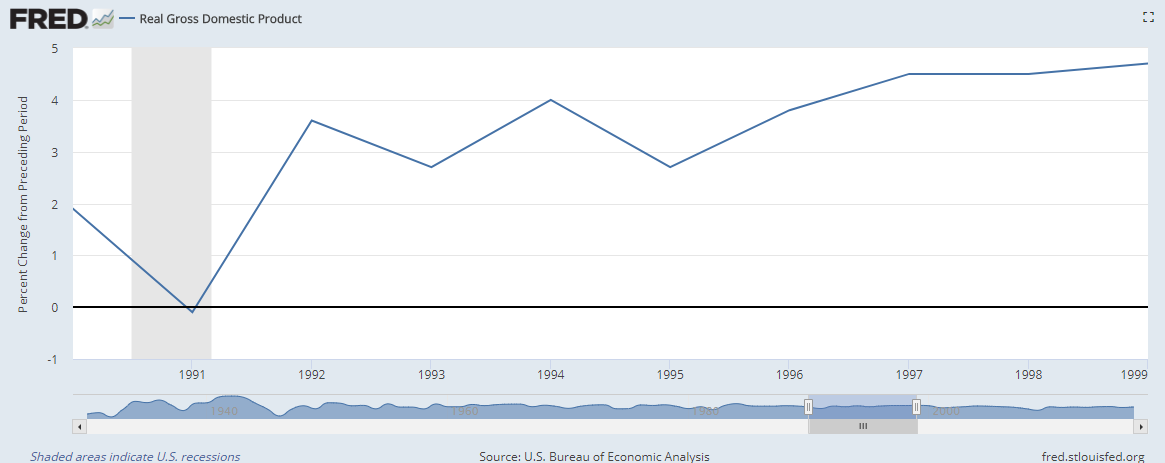

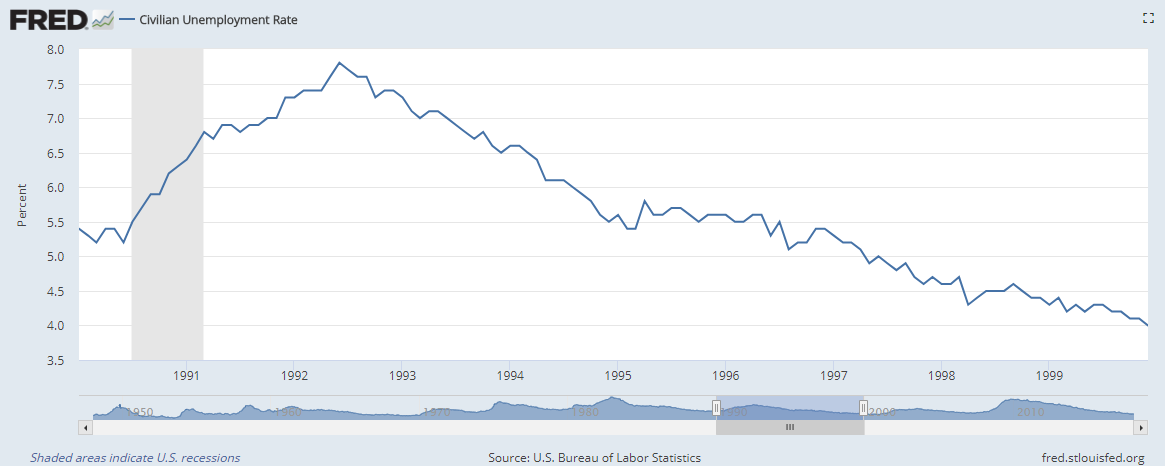

When times are good, many folks probably aren’t thinking all that much about what the government is doing with the chunk of their income it already takes. “We’re flying high; what’s the worry?” Think back a couple decades. 5% yearly increases in spending and “revenue enhancers” in the early 1990s produced budget deficits of almost 4% of GDP. After that figure dropped below 1% on the backs of reduced spending and tax reduction in the latter part of the decade, GDP averaged a point and a half higher while unemployment started dropping after flatlining around 5.5% mid-decade.

Rumblings could be heard about “shoring up social security,” paying down the $5+ trillion national debt, and the perennial favorite, “rebuilding infrastructure.” Would that have made sense? Possibly. There is some logic to it if you accept things the way they are.

But many don’t.

With the dot-com bubble deflating, and bringing a recession with it, a bipartisan congress passed W’s $1.35 trillion tax cut in 2001. Though it did have a Keynesian portion (remember the rebate checks?), it was supply-side in nature, with cuts in marginal and investment income rates. If a government insists on “fighting a recession,” which is a normal, healthy part of the business cycle, at least attacking it from this angle tends to provide the biggest bang for the buck in the long run, as opposed to spending measures orchestrated by government bureaucrats.

Paying down some of the aforementioned bills instead would have been construed by some as treating a symptom of what they see as the real problem; government spending.

--

“When you run in debt, you give to another power over your liberty.” – Benjamin Franklin, “Poor Richards Almanack [sic]”

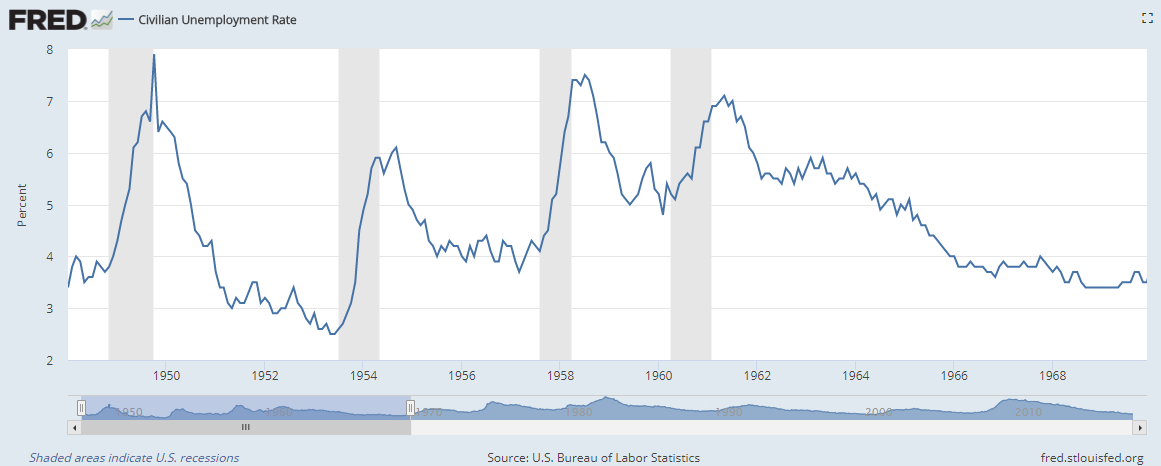

After World War II, much of the “New Deal” that had not already been ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court was abolished. President Truman’s own “Fair Deal” was largely rejected by congress, and President Eisenhower continued to hold the line on spending so that the “reduction of taxes … a very necessary objective of government” could be addressed.

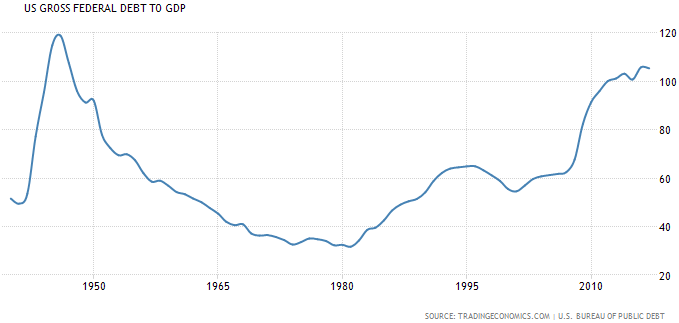

As a result, the budget remained largely in balance through the 1950s, the debt-to-GDP ratio kicked off a four-decade decline, and the unemployment rate averaged 4-5%.

It tends to erode individuals’ motivation to work. Why go punch a clock when the state can feed, house and entertain you? It also wears away the incentive of companies to produce high-quality, low-cost goods. Why go to the effort when the government will subsidize your operations, or protect you with trade barriers like tariffs or quotas?

Another problem arises when the public sector competes with the private sector for resources. When prices for inputs like labor or capital are bid up, the price of the final consumer good rises. Americans get hit twice when their income taxes essentially travel a “bridge to nowhere.” To make matters worse for example, whereas private stakeholders in DHL were able to cut their losses when the company pared back operations here until recently, American citizens are stuck with the regular losses of the U.S. Post Office.

Supporting all this spending requires a commensurate level of taxation. To pay those taxes, disposable income is diverted from otherwise productive endeavors, like investing in companies that employ workers, workers who need inputs from yet other companies to do their jobs. If this isn’t happening, people buy goods and services for themselves that are necessarily supplied by still other companies.

Moreover, the U.S. tax code is fairly complex, so much so there’s even debate about the number of pages. Regardless, Americans spend billions of hours and billions of dollars each spring to pay their bill. That's a deadweight loss to society.

When that still fails to bring in enough revenue for regular operations, government borrows.

--

“There is nothing so permanent as a temporary government program.” – Milton & Rose Friedman, “The Tyranny Of The Status Quo” (1984)

The budget surpluses that resulted from Eisenhower’s early spending restraint paved the way for President Kennedy’s income tax cuts, with the top rate dropping from 90% to 70%. Then came the advent of President Johnson’s (LBJ) “Great Society”: declaring “war on poverty” in 1964; the creation Medicaid and Medicare in 1965 and 1966, respectively; and increased federal spending on education in 1965.

Even though revenue surged by an annual average of 8% during this time, spending grew by 10-11%, with welfare, health and education outpacing that of defense. As we proceeded through the inflationary grind of the 1970s, the deficit climbed back over 2% of GDP.

Despite this, the debt-to-GDP ratio had sunk to its modern-day nadir of 31% when President Reagan took office.

Since then, according to U.S. Debt Clock.org, after dropping from almost 2/3 of the federal budget to just over 1/3 in 1990, health and income security entitlements have gradually crept back up to almost 60%. Defense spending has slid to an average of 21%.

By the time W signed off on reducing taxes, the “bills to be paid” had accumulated to push the national debt to 55% of GDP, while the accompanying interest obligation accounted for roughly 13% of the federal budget.

Incurring debt is not absolutely a bad thing. In fact, it’s generally advisable if the return-on-investment (ROI) is greater than the interest paid. Additionally, there’s a reason Uncle Sam is able to borrow so prolifically; investors regard it as one of the safest investments in the world. After all, if they’ll lend to some of the least economically-free countries in the world, throwing a line to #18 barely rates as a blip on the radar. Borrowing to fund consumption however, is recommended by nearly no one as a smart financial move.

Many of those who pushed for the tax reductions of 2001 and 2003 rejected “paying the bills” as is at the expense of lower taxation. Proper reform was, and still is needed.

--

“I should have understood that you want the government to give everyone free healthcare because you’re a good-hearted person who can’t do simple math.” – Roseanne to sister Jackie in the recently rebooted ABC comedy “Roseanne.”

Since social security’s introduction over eighty years ago, life expectancy has grown by roughly a decade, while the age to qualify for benefits has inched forward only two years, and even that reform required a 22-year lead time. Surely even the current beneficiaries, who no doubt contributed to the decades-long declining birthrate that has chipped away concurrently at the worker/retiree ratio, can see past such political scare-tactics as pushing grandma off a cliff to the need for reform.

For his part, W proposed allowing more personal control over a portion of what taxpayers pay into the system. It went nowhere.

Few issues fit the proverbial “definition of insanity” better than our approach to education. Uncle Sam has increasingly subsidized higher education with increasingly forgivable student loans, which very possibly contributes to an increasing skills mismatch. We’ve been spending more and more money on education at all levels since LBJ, including the creation of a cabinet-level agency under President Carter, and getting mediocre results at best.

In the absence of taking up serious proposals to free up the areas of education and health care, and redirecting responsibility to the ultimate beneficiaries, price inflation for these services has soared to as much as ten-times that of goods and services where the government footprint is much smaller, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Consumer Price Index.

In fact, we’ve regressed and arguably made the problem worse: adding prescription drug coverage to Medicare in 2003; the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001; and the expansion of Medicaid within the $1-2 trillion Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010.

In all, the federal budget has more than doubled during the first part of this century.

--

“Americans can always be trusted to do the right thing, once all other possibilities have been exhausted.” (loosely attributed to Winston Churchill)

After affirming that economists believe “ideal fiscal policy is counter-cyclical,” Cowen and Tabarrok address what they refer to as the “folk wisdom” of voters: “in bad times government should spend less and only in good times spend more.”

It’s debatable whether or not government should spend more in bad times, but it would seem even less so in good times. The economy would be expanding its potential GDP, unemployment would be low, wages solid, returns on investment healthy, etc. There’d be little reason for the public sector to pile on.

That there is “folk wisdom” about the government spending less in bad times makes more intuitive sense.

Common sense tells us that we should cut back on expenditures as much as possible when the economy turns south. That still might not be enough for those of us hit directly with a loss of income. In such a case, those who adhered to one of the most ubiquitous bits of financial advice, “saving for a rainy day”, are quite possibly miffed when government jumps in to bail out those who lived more profligately, beyond their means.

Ultimately, I believe history and the discipline of economics speak for themselves. To the former, I can point to the increased revenue that has resulted from every substantive tax reduction/simplification over the last century to show that the constitutional functions of government can still be adequately funded. And to the latter, all I have to do in class is stick to the basics and “keep it simple, stupid.”

A recent article in The Economist stated “good economics should involve using theory and data to quell prejudices.” The key is merely having a rudimentary understanding. Whether or not people choose educate themselves is another story.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed